Remembering David Bowie: The Eternal Icon and the Birth of MyEyecon “Stardust”

- Marco

- Dec 9, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Jan 2

David Bowie, the chameleon of rock, remains one of the most influential figures in music, fashion, and art even years after his passing in 2016. Born David Robert Jones on January 8, 1947, in London, Bowie reinvented himself countless times throughout his career, from the psychedelic folk of his early days to the glam rock persona of Ziggy Stardust, the soulful Thin White Duke, and the experimental sounds of his later albums like Blackstar. His ability to blend genres, challenge norms, and explore themes of identity, alienation, and futurism made him a cultural touchstone. Bowie wasn’t just a musician; he was a visual artist, actor, and innovator who collaborated with everyone from Brian Eno to fashion designers like Alexander McQueen. His impact on pop culture is immeasurable, inspiring generations to embrace change and creativity.

In 2025, as we approach the 10th anniversary of his death, Bowie’s legacy continues to spark new artistic tributes. One such creation is the “MyEyecon” artwork “Stardust”. The MyEyecon series is a personal homage by artist Marco that focuses on icons that capture the soul and spirit. “MyEyecon” plays on words—merging “my icon” with a focus on the eyes, whilst not referencing Bowie’s famous anisocoria on this occasion Marco has chosen to feature the other eye. Aniscoria is a condition that makes one pupil permanently dilated, giving the illusion of different-colored eyes: one blue, one appearing brown). In the case of Bowie this was caused by a school playground fight and a punch to the eye. The MyEyecon series explores themes of light and shadow, reality and illusion, much like Bowie’s own life and work.

The Process - Creating the MyEyecon Stardust while remembering David Bowie the eternal icon

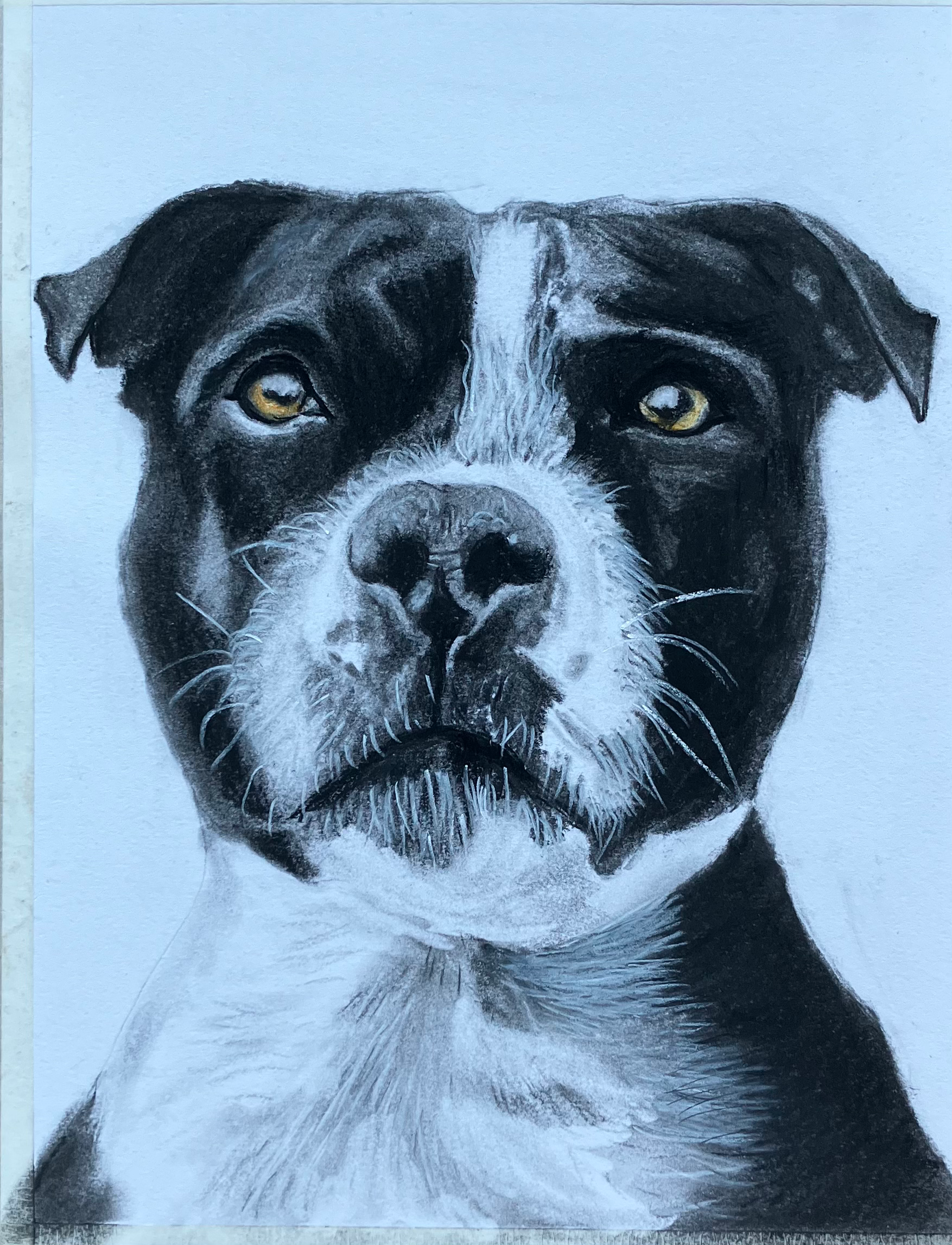

The MyEyecon Stardust artwork began as a study in contrast and expression, using traditional media like charcoal and pastels on a dark canvas to evoke Bowie’s mysterious aura. The process involved layering tones to build depth, starting with rough sketches and evolving into refined portraits.

One key image from the creation phase shows an early color iteration taped to a workspace surface. Here, Bowie’s face emerges from the blackness, with sharp highlights on the skin and a piercing green eye that adds an otherworldly vibe—perhaps a artistic liberty to symbolize his alien-like personas from albums like The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust. The hair is textured and wild, the expression intense and introspective, capturing that signature Bowie stare that could pierce through time.

The final piece, signed “Marco 25,” refines this into a striking black-and-white composition. The left side of the face is illuminated, fading into deep shadows on the right, emphasising the duality that defined Bowie’s career. The subtle blending of whites and grays creates a dramatic emergence from the void, much like how Bowie appeared in the cultural landscape—bold, innovative, and always half-hidden in mystery. This artwork not only pays tribute but also invites viewers to reflect on their own icons.

These images document the hands-on evolution: from experimental color tests to the polished monochrome finality, showcasing how a simple reference can transform into something profoundly personal.

Would Bowie have objected to Marco using his likeness to create this artwork well that leads on to the other part of this blog, fair use and legality.

Why Artists Can Use Photo Images of Celebrities: Navigating Fair Use

Artists often draw inspiration from celebrities like Bowie, using photographs as references to create original works. But is this legal? In the United States, the answer hinges on copyright law and the doctrine of fair use, which allows limited use of copyrighted material without permission for purposes like criticism, commentary, education, or transformative art. In the MyEyecon series all artworks are original and are drawn by Marco using several reference public domain photos, mainly to ensure correct eye colours, one of the only coloured elements in each artwork.

Fair use is evaluated on four factors: the purpose and character of the use (e.g., is it transformative or commercial?), the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount used, and the effect on the market for the original. For instance, if an artist uses a celebrity photo merely as a reference to create a new, original drawing—like reinterpreting it in a different style or medium—it can qualify as transformative, adding new expression or meaning. This is common in pop art, where figures like Andy Warhol turned photos into iconic silkscreens.

However, it’s not without risks. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2023 ruling in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith clarified that “transformative use” doesn’t automatically apply if the new work serves a similar commercial purpose as the original photo, such as licensing for magazines. In that case, Warhol’s orange silkscreen of Prince was deemed not fair use because it competed directly with the photographer’s market. Fair use acts as a defense in court, not a shield against lawsuits, so artists should be cautious.

To stay safe, many artists opt for public domain images, licensed stock photos (e.g., from Getty Images for celebrities), or create entirely from imagination. If the artwork is non-commercial, educational, or significantly altered—like MyEyecon’s stylized portraits—it strengthens the fair use argument. Ultimately, while celebrities’ likenesses also involve right of publicity laws (varying by state), using a photo for inspirational, transformative art is often permissible, fostering creativity without stifling it.

Bowie himself was a master of reinvention, borrowing from art, film, and culture to craft his personas. Works like MyEyecon keep that spirit alive, reminding us why icons endure. If you’re inspired, grab a sketchpad—who knows what you’ll create next?

Understanding the Use of Celebrity Images Under UK Law

The use of a celebrity’s image in the UK is governed by a patchwork of laws rather than a single, comprehensive “right of publicity” or “personality rights” framework found in jurisdictions like the United States or France. Unlike the US, where celebrities (or their estates) can control commercial exploitation of their likeness for decades after death, UK law relies on indirect protections such as copyright, passing off, data protection, and misuse of private information. This creates variability depending on the context: artistic or non-commercial uses may face fewer hurdles, while commercial exploitation (e.g., advertising) carries higher risks of legal challenge.

As of December 2025, the UK government is consulting on potential reforms, particularly in light of AI-generated deepfakes and digital replicas, which could introduce explicit personality rights to give individuals more control over their image. For now, however, the law emphasizes balancing freedom of expression (under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights) with privacy (Article 8).

Key Legal Frameworks and How Use Varies

1. Copyright Law (Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988)

Copyright protects the photograph or image itself, not the celebrity’s likeness. If you’re using a photo of a celebrity, you need permission from the copyright holder (usually the photographer), unless it qualifies as “fair dealing” for purposes like criticism, review, or news reporting. In this blog and on the MyEyecon web site I have made it clear that the artwork is not endorsed by David Bowie or his estate. It is a transformative piece and should be considered fair use.

• Variation: Non-commercial artistic uses (e.g., a transformative painting or parody) are more likely to be fair dealing if they add new meaning and don’t harm the market for the original photo. Commercial reproduction (e.g., printing on merchandise) requires a license, even if the image is public domain. Celebrities rarely own the copyright unless they commissioned the work. Again as the MyEyecon “Stardust” has been greatly modified/transformed. Plus, of course, Bowie has unfortunately deceased.

2. Passing Off (Common Law Tort)

This prevents unauthorized use that implies celebrity endorsement, damaging their commercial goodwill. To succeed, the celebrity must prove: (i) established goodwill in their image; (ii) public misrepresentation (e.g., suggesting approval); and (iii) resulting harm (e.g., lost endorsement fees). Cases like Irvine v Talksport (2002) established that altered images falsely implying endorsement can be actionable.

• Variation: Strongest for commercial contexts like ads or products; weaker for editorial or artistic uses without endorsement implications. Non-celebrities have little recourse here, as it requires proven commercial goodwill.

3. Data Protection (UK GDPR)

Images of living individuals are “personal data,” so processing (e.g., publishing) must be lawful, fair, and transparent. Consent is ideal, but alternatives like “legitimate interests” (e.g., public interest journalism) may apply.

• Variation: Permitted for non-commercial or journalistic uses in the public interest; commercial uses without consent risk fines or erasure demands. Applies only to living celebrities.

4. Misuse of Private Information and Breach of Confidence

Protects against disclosure of private images, balancing privacy with public interest. Celebrities expect more scrutiny but can claim if images were taken in private settings (e.g., Douglas v Hello!, 2005).

• Variation: Relevant for intrusive uses (e.g., paparazzi shots in ads); irrelevant for public-domain images or public events. Defamation may apply if use harms reputation.

5. Trade Marks and Advertising Standards

Celebrities can register names, logos, or likenesses (e.g., David Beckham’s name for perfumes) to block confusing uses. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) codes require consent for implied endorsements and prohibit offensive portrayals.

• Variation: Primarily commercial; non-advertising artistic works are unaffected unless trademarked elements (e.g., a signature) are copied.

Practical Advice and Emerging Trends

• Artistic vs. Commercial Use: Transformative art (e.g., a stylized portrait like the Bowie homage discussed previously) is often safer under fair dealing, but selling prints could trigger passing off if it implies endorsement. Always obtain permissions to mitigate risks.

• AI and Future Changes: Deepfakes highlight gaps; the ongoing consultation (closed February 2025) may lead to new IP-like protections for voices and likenesses, similar to Denmark’s 2025 law.

• Compared to the US:

UK protections are narrower, less postmortem, and more fact-specific, favoring expression over absolute control.

In summary, UK law varies by use case—lenient for public-interest or transformative purposes, stringent for commercial ones. Consult a lawyer for specific scenarios, as outcomes depend on context. This flexibility fosters creativity but can leave creators vulnerable to disputes.

Comments