When a portrait is not just a likeness but an act of remembrance - Group Captain Paddy Hemingway. The Last of the Few.

- Marco

- Sep 21, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 21, 2025

RECENT UPDATE

I have decided to release 10 A4 Giglée Prints and 5 A3 Giglée Prints of the Artwork detailed below. ALL PROCEEDS WILL BE DONATED TO THE RAF BENEVOLENT FUND.

THIS IS A LIMITED OFFER AND WILL NOT BE REPEATED SO SHOULD YOU WISH TO SUPPORT THE BENEVOLENT FUND AND PURCHASE ONE OF THE PRINTS PLEASE CLICK HERE. PRINTS COST £30 Exc Postage & Packaging

Capturing a Legend in Charcoal and Pastel: Group Captain Paddy Hemingway

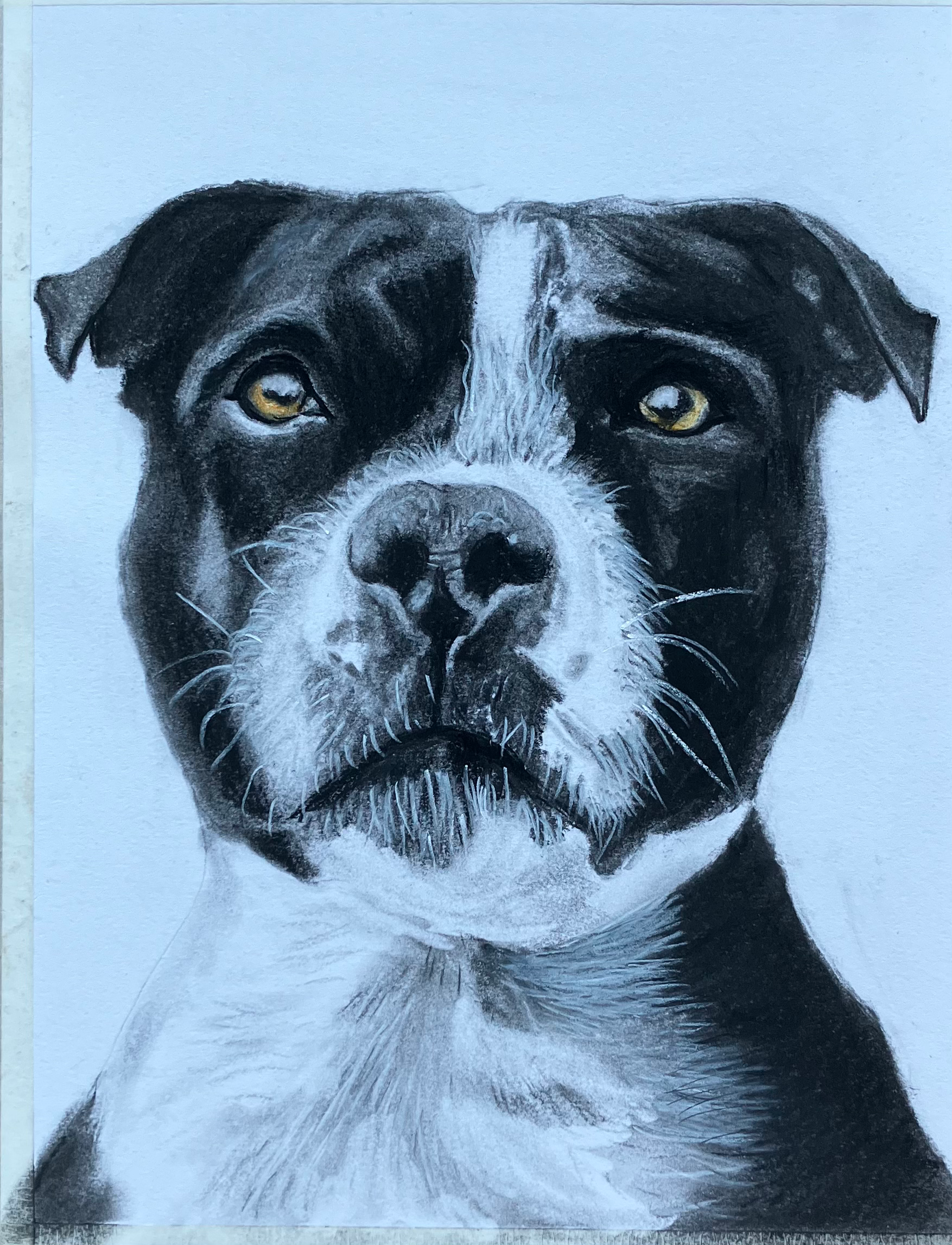

There are moments in art when the subject transcends the canvas—or in this case, the textured surface of paper. My recent work, a charcoal and pastel portrait of Group Captain Paddy Hemingway, is one such moment. As the last surviving Battle of Britain fighter ace, Hemingway represents not only personal courage but also the collective spirit of resilience and sacrifice. Not only was Group Captain Hemingway shot down four times, and survived, his plane taking him to receive his latest medal also crashed. Again he survived to tell the tale. In his final bale out from his stricken aircraft he managed to break his arm on the tail as it went passed. Paddy himself softened his landing in a tree.

Why Charcoal and Pastel?

I chose charcoal and pastel for this piece because of their unique ability to balance strength with delicacy. Charcoal, with its deep, rich blacks, brings a gravity and permanence fitting for a man of such stature. Pastels, on the other hand, introduce warmth and subtlety, allowing me to capture the softness of expression, the sparkle in the eyes, and the muted tones of a well-worn uniform. Together, they provide the perfect medium to honor both the toughness of a fighter pilot and the humanity of the man behind the medals.

The Process

I began by studying photographs of Paddy Hemingway, focusing on the lines of his face—lines carved by years of service, wisdom, and experience. Each crease tells a story, and in charcoal, those stories become bold and unmistakable.

The cap and uniform presented a chance to introduce structure and formality, while the medals demanded a lighter touch of pastel, their glint catching the viewer’s eye without overwhelming the portrait. For the background, I kept things minimal, letting the subject command the space as he once commanded the skies.

More Than a Portrait

This artwork is not just a likeness—it is an act of remembrance. Every mark of charcoal is a nod to history, every stroke of pastel a tribute to endurance. In creating this portrait, I wasn’t just drawing Paddy Hemingway the man; I was attempting to capture Paddy Hemingway the symbol—an enduring link to a generation that defended freedom at unimaginable cost.

Final Reflections

When I stepped back from the finished work, I saw more than the face of a distinguished airman. I saw a bridge between past and present. My hope is that viewers feel the same—that they not only recognize Paddy Hemingway, but also pause to reflect on the stories and sacrifices carried by his generation.

Art can preserve memory in a way words cannot, and I am humbled to have created this small tribute to a man whose life is part of history’s greatest story.

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating a Charcoal & Pastel Portrait

1. Gather Your Materials

Paper: Heavyweight, textured paper (at least 160gsm). Toned grey or cream works beautifully with both charcoal and pastel.

Charcoal: Use a mix of willow (soft, for broad areas) and compressed charcoal (dark, sharp lines).

Pastels: A limited palette—flesh tones, muted blues, greys, and a touch of metallic pastel or chalk for medals.

Erasers: Kneaded eraser (for subtle lifting) and a precision eraser (for highlights).

Fixative spray: To preserve layers without smudging.

Blending tools: Stumps, tissues, or even fingers for softer transitions.

2. The Initial Sketch

Begin lightly with willow charcoal, sketching the basic proportions of the head and shoulders.

Keep lines loose—this stage is about structure, not detail.

Place the cap and medals early, as they frame the character of the portrait.

3. Blocking in Shadows

Use the side of the charcoal stick to establish broad shadow areas: under the cap, around the jawline, and in the folds of the uniform.

Think of light direction—choose one consistent source (e.g., top left) to create depth and realism.

4. Building Mid-Tones and Texture

Blend the charcoal with a stump to soften transitions.

Introduce pastel skin tones gradually—peach, ochre, and muted pinks—layered over charcoal for richness.

Pay special attention to the eyes: add highlights with a kneaded eraser before introducing subtle pastel color.

5. Refining Details

Use compressed charcoal for sharp edges: the cap badge, medal outlines, and crisp uniform folds.

Pastels should be applied sparingly here—metallic or light tones for medals, pale blue/grey for the RAF uniform.

Lift highlights (such as the gleam in the eyes, or shine on medals) with an eraser for contrast.

6. Final Touches

Step back frequently to judge balance. Too much pastel can overpower—charcoal should remain the backbone.

Use soft pastels in the background only if needed; otherwise, keep it minimal to let the subject dominate.

Apply a light mist of fixative between layers, and a final coat at the end to prevent smudging.

7. Reflection

Take time to sit with the portrait. Ask yourself:

Does it convey strength and dignity?

Do the eyes feel alive and human?

Does the balance of shadow and color honor the subject’s story?

More than a technical execution

Art is more than technical execution—it’s about presence. In portraying Paddy Hemingway, I was not only sketching a face, but also preserving the memory of a generation who fought for their values.

Comments